« Reading the "Augmented" Digital Text: AR Volcano | Main | Learning Language Pronunciation »

January 6, 2006

Narrative Structure and Medium: "The Red Planet" and the Future of the Educational DVD-ROM

As we've noted before in Next/Text, a key question in considering the future of the digital textbook is whether the text should be delivered to the user via the web or on a disc. In the 1990s -- when Voyage pioneered the development of the educational CD-ROM -- the choice was clear: accessing video and audio was far too difficult to make developing web content worthwhile.

Since the demise of Voyager, however, the production of disc-based educational material has gradually decreased, and it has become less clear that ROM discs are the medium of choice for delivering "thick" multimedia content. As some of the examples we've written about (especially the WebCT film course and the MIT Biology class) demonstrate, streaming video can be easily integrated into online instructional material: there's still much room for improvement, but it's clear that online video and audio delivery will only improve over time.

So what is the future of the disc-based educational text? The question seems especially relevant now that the recent industry debate over the formats of next-generation DVDs has provoked more than a few technology analysts to wonder aloud whether discs themselves are a doomed delivery medium. I'm not completely convinced by these arguments, as I feel that, as far as educational media are concerned, there may still be good reasons to put things on disc. In what follows, I'll be weighing the pros and cons of scholarly work on DVD-ROM through a discussion of The Red Planet, a DVD-ROM project published in 2001 by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

The Red Planet is the first publication in Penn's Mariner 10 Series, a publishing venture that represents the first attempt by a university press to publish scholarly work on DVD-ROM. The titles chosen for this Penn series are interdisciplinary studies that blend what C.P. Snow might call the "two cultures" of science and the humanities; each also includes a wide range of textual, visual and audio resources. Thus far, in addition to The Red Planet, Penn has published a volume on humanistic approaches to medicine; a physics text, "The Gravity Project," is forthcoming.

Interestingly, The Red Planet has its roots in an unsuccesful venture in online education: project co-author Robert Markely was first approached to do a series of video interviews to be embedded in a web course about science fiction. When that project fell through in 1997, Markley realized that such interviews would be an ideal first step towards creating a digital scholarly text that explored the roles Mars has played in 19th and 20th century astronomy, literature and speculative thought. Teaming up with multimedia designer/theorists Helen Burgess (also a co-author for Biofutures, a DVD-ROM-in-progress that I've previously discussed) Harrison Higgs and Michele Kendrick, Markley approached Penn with his idea for the project.

After getting the go-ahead from Penn -- and substantial funding from West Virgina University and Washington State University -- the group spent more than four years completing the project. Markley wrote a 200-page monograph on cultural and scientific approaches to Mars divided into nine chapters -- Early Views; The Canals of Mars; The War of the Worlds; Dying Planet; Red and Dead; Missions to Mars; Ancient Floods; Dreams of Terraforming, and Life On Mars. He and others in the group in the group then interviewed science fiction writers including Kim Stanley Robinson, cultural critics such as N. Katherine Hayles and a diverse group of major scientific figures including Richard Zare, Carol Stoker, Christopher McKay and Henry Giclas (the Giclas interview is pictured below). They also assembled hundreds of current and archival photos, quotations from scientific and literary texts, dozens of clips from science fiction films, and an impressive array of diagrams explaining key concepts in astronomy. And to complement the DVD-ROM project, they authored a website with educational resources, a timeline, and updatable discussions of debates about Mars exploration.

The success of The Red Planet stems from the fact that all of this multimedia does not serve simply to gloss on Markley's monograph: it changes Markley's own authoring process as well. As Markely points out in a chapter he wrote on the project for a book titled Eloquent Images, his main challenge was to create a work that was scholarly enough to be considered worthy by tenure committees, a requirement that has been a serious hurdle to the willingness of academics to invest time and effort in the creation of digital scholarly work. "The majority of commercial educational software treats content as a given," Markley wrote, "reified as information that has to be encoded within a programming language and designed in such a way as to enhance its usuability." To Markley, moving beyond this "usable information" paradigm, involved more than just foregrounding the text: it meant that the designers should make a significant contribution to the intellectual shape of the project that extended beyond usability issues and promoted them to the status of co-authors.

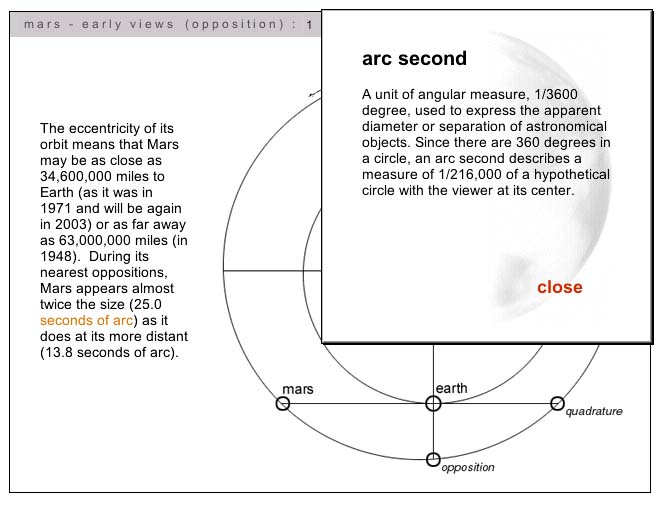

With this in mind, Markley and his co-authors worked collaboratively to develop a navigation structure for the project that reflected both scholarly and pedagogical concerns. The resulting interface eschews the hypertext structures of many web-based projects and relies instead on a chronological narrative structure that the authors felt best maintained the integrity of the scholarly text. In other words, hyperlinks don't move the user around inside the central text, but rather lead to film clips or selections of explanatory material (such as the diagram illustrating the term 'arc second,' pictured below).

The structure of The Red Planet thus resembles, in some ways, the structure of Columbia University's Gutenberg-e publications: if the reader chooses, they can read straight through the text and ignore the linked explanations and supporting material. For the most part, video interviews open on seperate pages and launch automatically (the screenshot above actually shows an exception to this), but the reader can always use the forward navigation key to advance the narrative.

The Red Planet demonstrates that this text-centric approach to digital scholarly work need not come at the expense of the quality of multimedia integrated into the project. From the beginning, Markley and his collaborators wanted The Red Planet to be a standout in terms of both the amount and the quality of supporting media. This, in turn, determined their choice of medium: in writing grant proposals to fund the development of the project, Markley stressed the importance of using DVD-ROM instead of CD-ROM to construct the volume. At the time The Red Planet was produced, the disc was able to hold about six times more data than a traditional CD-ROM; it was also able to read this data about seven times faster, meaning that the video segments played much more smoothly and were of far higher quality. As Markely wrote in his chapter for Eloquent Images, "video on CD-ROM is a pixilated, impressionistic oddity: on DVD-ROM, video begins to achieve something of the semiotic verisimilitude we associate with film."

The DVD-ROM format also allows The Red Planet'sdesigners to incorporate much longer video clips into their project: interviews are up to five minutes in length, and video clips are the maximum length allowable under fair use. In the case of the interviews, the longer interviews allow for detailed explorations of the question at hand: in the case of the film clips, the expansiveness of the selections gives the viewer a sense that they are experiencing a portion of the actual film rather than a snapshot.

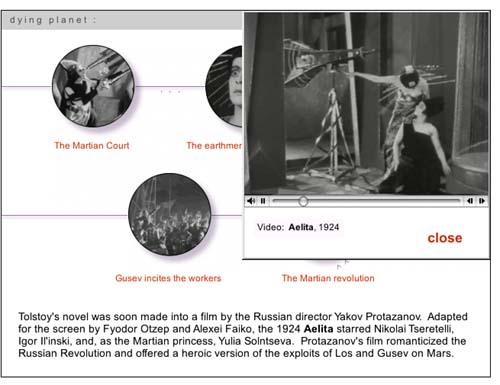

Still, though the videos are high quality, they are not full screen (as shown by the screenshot above, which shows a page that features a series of clips from the 1924 Russian film Aelita). The limited size of the clips is one of a series of tradeoffs Markley and his team found they had to make when confronted with their own limited budgets and realistic pricing expectations for their DVD-ROM. In his chapter for Eloquent Images, Markley writes:

In authoring The Red Planet, we were caught in an ongoing process of having to decide what we could afford in time, money and labor to live up to our grant application claims that DVD ROM could do what neither CD Rom nor the web could manage: integrate hours of high-quality video into a scholarly multimedia project. At the same time, we had to engineer downward the minimum requirements of RAM, operating systems, monitor resolutions, etc to avoid pricing our project out of the mainstream educational market.

Markley's point is an important one: DVD-ROMs have the potential to deliver amazing multimedia content, but that is simply the capacity of the medium. A successful DVD-ROM author not only has to find the time, money, and skill to produce the project; they also have to operate within the constraints of a market which is increasingly accustomed to getting educational content online for free. In the end, The Red Planet was probably more successful at the former than the latter: as a example of the genre, it is exceptional both in content and design, yet the disc has yet to find the wide audience of both scholars and Mars enthusiasts that its authors had hoped it would find.

Looking at The Red Planet and reading Markley's theorization of the work done by his team, I'm impressed by their very self-reflective effort to author a major project over several years in the midst of a rapidly shifting new media landscape. I'm convinced by Markley's argument claims in Eloquent Images that the DVD-ROM format allows multimedia authors to create projects that are more narrative-centered, and thus also, perhaps, more scholarly and more acceptable to the legitimating bodies of academia. At the same time, I'm unsure what will happen to the market for such work: either we will see a critical mass of DVD-ROMS emerge that will create a critical mass of reader/users, or the format will atrophy as the web becomes more and more the preferred method of distribution. Markley himself is aware of the uncertain future of projects such as his own: while making the case for The Red Planet as the best fit between form, content and medium, he also notes that the project is less "a model to be emulated" as much as it is "a historical document, a means to think through the scholarly and professional legitimation of video and visual information."

So should scholars persist in authoring in the medium? I think so, as long as they take a clear-eyed view of its advantages and pitfalls, and as long as they realize -- as Markley and his team did all along -- that while the time and effort spent on a DVD-ROM project is greater than the time spent on a traditional academic monograph, the audience might ultimately be more limited. Not always: a project such as the Biofutures DVD (discussed in an earlier post), which has been developed with a very specific pedagogical aim, might find a more extensive academic audience even if it doesn't find a non-academic one. The same might be said for Medicine and Humanistic Understanding, the newest title in the Mariner 10 series. The key is finding a way to create a new media object that is stable enough to allow users to take advantages of its merits both now and in the foreseeable future.

Posted by lisa lynch at January 6, 2006 2:37 PM